Legacy of Thaddeus Stevens

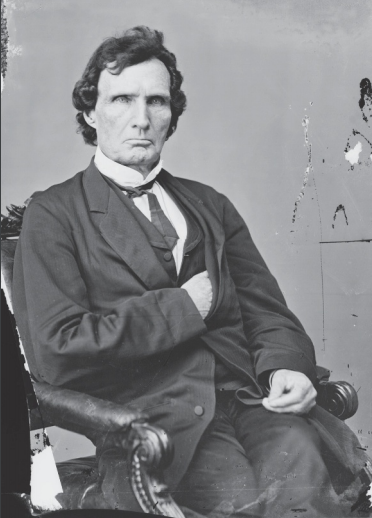

Thaddeus Stevens was born in Danville, Vermont, on April 4, 1792. He was the second of four boys whose parents were Sarah and Joshua Stevens. Thaddeus’ older brother, Joshua, was born with two clubfeet that made it very difficult for him to walk. In the late 1700s, any physical deformity was seen as a sign from God that the family had committed some serious sin. Such a deformity was called the mark of the devil, and as a consequence, the family was ridiculed and shunned. The family’s status worsened when Thaddeus was also born with a clubfoot. Thaddeus’ father, Joshua Stevens, was an alcoholic and an abusive man. The family lived in abject poverty on a small farm. By the time Thaddeus was 12, his father had abandoned the family and was later killed in the War of 1812. Sarah Stevens was a kind woman with great energy, a strong will, and a devout faith in God. She held the family together by working day and night. In addition to the farm work, she cleaned and performed other domestic chores for her neighbors. Thaddeus loved his mother and was devoted to her throughout his life. Sarah realized that the best hope for her eldest sons was education. She scraped together enough money to enroll them in the nearby one-room Peacham School.

|

Thaddeus was frail, raised in poverty, and lived with a challenging physical disability. Consequently, he was teased mercilessly by other children throughout his childhood. Extremely sensitive, he became very shy; however, he excelled in school. It became obvious that he possessed a great intellect and had a special aptitude for debating. Upon completion of his education at Peacham, Thaddeus was accepted at Dartmouth College. He was the least wealthy student at the College, never having enough money for books let alone money to socialize with his rich classmates. As a result, he was an outcast, just as he had been throughout his childhood. Even though he was more qualified than most of his peers, he was not nominated for Phi Beta Kappa, an honors fraternity. This insult left him hurt and bitter.

Thaddeus Stevens graduated from Dartmouth and accepted a teaching position at a one-room school in York, Pennsylvania. He studied law in the evenings and passed the bar exam in a year. He set up practice in Gettysburg and later moved to Lancaster. He became an instant success. In his first year, he successfully argued nine out of ten cases before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, an unprecedented feat. Word of his ability and success spread throughout the region, and he was inundated with clients. After five years, he owned a house and lot, several other properties, and was able to purchase for his mother a 250-acre farm with 14 cows. He said that buying her the farm was the “greatest satisfaction of his life.”

|

During the next 21 years, he would become very wealthy and became known as an excellent attorney, renegade politician, and philanthropist. In 1833, Thaddeus Stevens was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. He did not run as a Democrat, the party that dominated Pennsylvania politics, but rather as an Anti-Mason. This was a political party that opposed Freemasons or Masonry. Freemasons were an organization that included many of the most influential and prestigious men of the time, including George Washington. Anti-Masons opposed it because of its secrecy, oaths, and religious pageantry. Stevens objected to Masonry because of his personal hatred of exclusionary clubs and societies and because some chapters’ charters excluded “cripples.” During his time in the General Assembly, the accomplishment Thaddeus Stevens was most proud of was his effort to institute free public education. In 1830’s America, there were practically no free public schools. Those that existed were found in New England and in large cities. Only affluent families could afford to send their children to school. In a few places, poor children could attend school if their parents would publicly admit poverty; however, this was very rare.

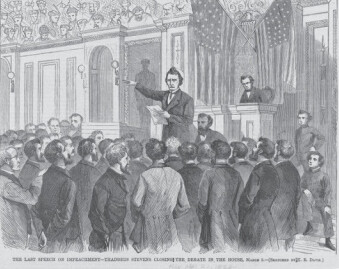

When a Free School Bill was introduced in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, Stevens became an ardent supporter. He collaborated with Governor Wolfe to get the bill passed, even though Wolfe was a Mason. However, when the legislators returned to their districts there was an uproar. Some people believed that free public education was too expensive while others opposed the bill because they had their own religious schools. Over 32,000 individuals signed a petition to repeal the new legislation. The General Assembly was recalled and went into session to reconsider. The Senate quickly passed a repeal bill. The bill then went to the House. Stevens took the floor to defend the original bill. There was standing room only as most of the Senate filled the gallery. Stevens began his speech by using statistics to show how a state system of free schools was more efficient and ultimately less costly than the existing system. He said the repeal act should be called: “An act for branding and marking the poor, so that they may be known from the rich and the proud.” He went on:

“I know how large a portion of the community can scarcely feel any sympathy with, or understand the necessities of the poor; the rich appreciate the exquisite feelings which they enjoy, when they see their children receiving the boon of education, and rising in intellectual superiority above the clogs which hereditary poverty had cast upon them.... When I reflect how apt hereditary wealth, hereditary influence, and perhaps as a consequence, hereditary pride, are to close the avenues and steel the heart against the wants and rights of the poor, I am induced to thank my Creator for having, from early life, bestowed upon me the blessing of poverty.”

He urged the legislators to ignore the misguided petitions and to lead their people as philosophers, with courage and benevolence. After he finished he limped back to his seat to the cheers of the entire assembly. The House suspended the rules and amended the Repeal Bill into an act that actually strengthened the original Free School Act and passed it. The Senate immediately followed suit. The result was to give Pennsylvania a statewide, free public school system an entire generation before New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and the entire South. This is why Stevens is referred to as the savior of free public education in Pennsylvania, and why the Commonwealth created Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology as a tribute to Thaddeus Stevens. The free public school system is another example of Stevens drawing from his own background and experience and attacking privilege based on anything other than merit. Also, it reflects his fundamental belief that education is the great equalizer. He later said that if education is inexpensive and honorable, people with intelligence—no matter how poor— would utilize it to improve themselves.

An important part of Thaddeus Stevens’ legacy is his philanthropy. Throughout his life, he could never recall the poverty and discrimination of his childhood without great pain. Its effect was to sensitize him to the oppression and human suffering in the world. He simply could not bear to hear or see suffering if his money or legal aid could relieve it. He gave of them both almost without limit. He did this irrespective of race, religion, national origin, or political affiliation. Even his harshest critics said he was charitable, kind, and lavish with his money in the relief of poverty. He had standing orders with his physician and cobbler to treat all deformed and disabled children at his expense. It is impossible to estimate how much money he gave to the poor and needy or the value of the legal services he provided for free. One indicator was that at the time of his death, he had over $100,000 in notes from individuals to whom he had loaned money, money which had never been repaid.

In his will, he left $50,000 to establish a school for the relief and refuge of homeless, indigent orphans. This original bequest has evolved into Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology. His will states:

“They shall be carefully educated in the various branches of English education and all industrial trades and pursuits. No preference shall be shown on account of race or color in their admission or treatment. Neither poor Germans, Irish, or Mahometan, nor any others on account their race or religion of their parents, shall be excluded. They shall be fed at the same table.”

|

He defended and supported Native Americans, Seventh-day Adventists, Mormons, Jews, Chinese, and women. However, the defense of runaway or fugitive slaves gradually began to consume the greatest amount of his time, until the abolition of slavery became his primary political and personal focus. He was actively involved in the Underground Railroad, assisting runaway slaves to get to Canada, as many as 16 a week. Thaddeus Stevens was elected to the United States House of Representatives from 1849–1853 and from 1859 until his death in 1868. This was the period leading up to and including the Civil War and the beginning of Reconstruction. During this time, Stevens became the most powerful congressman in Washington. He chaired the House Ways and Means Committee and later the Appropriations Committee. He was responsible for funding the war effort and later Reconstruction. |

|

His goals during this period were the following: (1) the abolition of slavery; (2) full legal rights regardless of race; (3) voting rights regardless of race; (4) and the result of Reconstruction to be the empowerment of African Americans by redistributing power and wealth in the South. Stevens’ legislative legacy is the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, which serve as the basis for all civil rights legislation.

Stevens drafted his own version of the 13th Amendment, but when it failed to gain support, he shepherded a more popular version through Congress. It ended slavery in all states, whereas the Emancipation Proclamation only abolished slavery in the Confederacy. Stevens also guided the 14th Amendment through Congress. This Amendment established a national citizenry with all citizens given equality before the law, which no state could alter. He was disappointed because the Amendment still made references to males only, allowed states to restrict voting rights based on race, and allowed Confederates to vote. Stevens’ disappointment in the shortcomings of the 14th Amendment paled in comparison to his outrage over the failure of Reconstruction at the end of the Civil War. He wanted the wealthy white political power structure of the South to be dismantled and redistributed. He proposed that every black free man should receive 40 acres and a mule and that Confederates should not be allowed to vote immediately.

Unfortunately, any chance of Stevens’ vision becoming a reality was lost when Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson, the vice president, became president. Johnson’s views about the nature of Reconstruction are reflected in this quote from his annual address to Congress in 1867. Stevens hated Johnson and worked to have him impeached. While the final vote fell one vote short in the Senate, Johnson was permanently weakened and reduced to a figurehead for the remainder of his term, being replaced by Ulysses Grant in 1868.

Stevens did not live to see the passage of the 15th Amendment; however, most would agree at the very least he inspired it. It guaranteed all male citizens the right to vote. Thaddeus Stevens died at midnight on August 11th, 1868. The public expression of grief in Washington was second only to Lincoln’s. His coffin lay in State at the Capitol Rotunda, flanked by a Black Union Honor Guard from Massachusetts. Twenty thousand people, one-half of whom were black free men, attended his funeral in Lancaster. He chose to be buried in the Shriner-Concord Cemetery because it was the only cemetery that would accept all races. He wrote the inscription on his headstone that reads: